Today we look at the 11th to the 18th of September in the diary of Margaret Emily Shore (1819-1839). I previously shared her journal entry from 31 July 1832 and a week in her 1837 journal. She was born in Suffolk as the eldest of five children. She died of consumption when she was only nineteen years old. Fifty years after her death, her two younger sisters Arabella and Louisa, who were both poets and writers, published a carefully curated selection from Emily’s diaries.

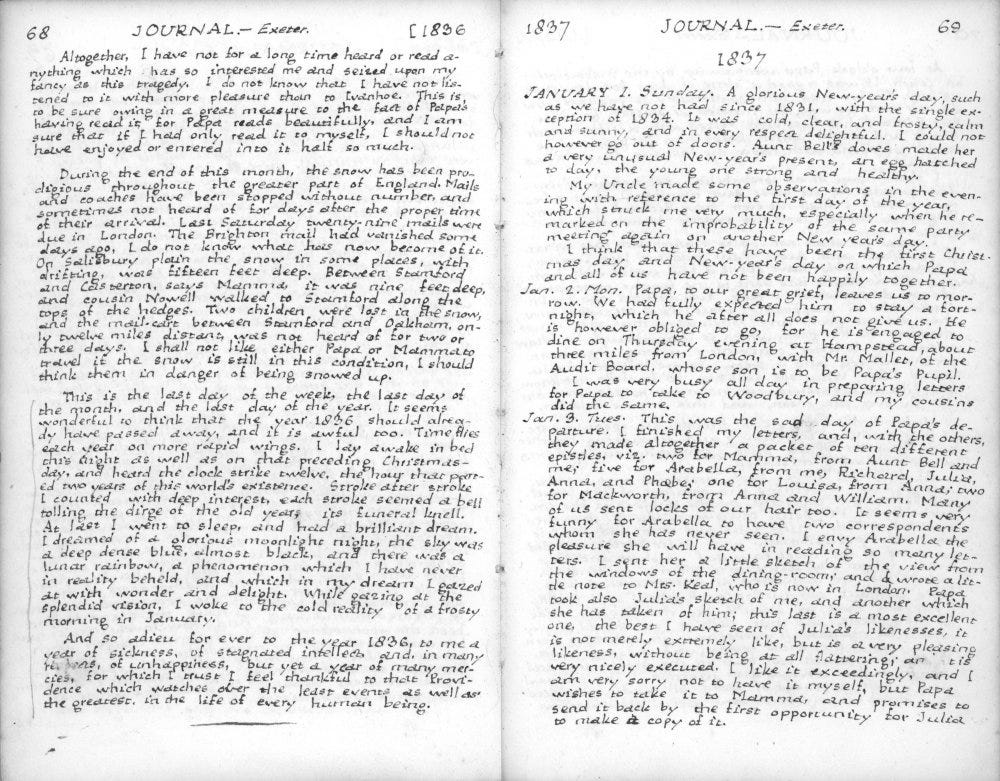

In the 1980s, the University of Virginia Press re-published the diaries, including parts of them that had not been included in the earlier edition. See here for an absolutely fascinating backstory of this re-publication, written by Barbara Timm Gates, who found a volume of the first publication of the diaries and decided to look for the original manuscripts.

At the time of this week’s entries in 1836, Emily was struggling with her health, as she was for a large portion of her life.

16 October

I went to church to day, the first time I have been able to go for five months. It was St. Sidwell’s Church; we went in the afternoon, and heard Mr. Tripp, who I believe is a very excellent clergyman, but he has a dull heavy appearance, a great deal of dialect, and an unfortunate delivery. I was greatly struck and much affected by the singular (was it not providential?) circumstance, that on this occasion, the very first on which I have been able from long continued illness, to attend worship in the House of God,- that the sermon should have been on the text, “Whom the Lord loveth, he chasteneth,” and that the subject should have been the advantages and blessings to be derived from sickness. It was a very good sermon, though short.

St. Sidwell’s is a modern church, built in the Gothic style, and it is done, I think, with great taste. It is a pretty good-sized, and very elegant building. The exterior is light, and the stone of a good colour, not deformed with white-wash; of the interior I did not see much, as we were but just in time, but it seemed to me to be richly ornamented, and not in a bad style. The organ and singing are very good. We sat in the gallery; it was a close day and a crowded church, and we found it intensely hot. I found my shortness of breath return a little, and I was tired with my walk, but I do not think I got any harm by it, and I was much gratified at being able to go to church.

17 October

Mamma went away to day, leaving me here, for seven months, a hundred and seventy-one miles from home. But I think I shall be as happy here as I can ever anywhere away from home, for Aunt Bell is exceedingly kind, and I love my cousins very much. Mamma travels in the most convenient way possible, for Papa’s cousin Bulkely Praed takes her to London in his own carriage, and there she will take up her quarters with the Malkins, who have removed from 12 Welbeck Street to 21 Wimpole Street.

There was a fog all day, continually increasing, so that I could not go out, and I am afraid Mamma has had a disagreeable day’s journey.

18 October

I sat for an hour and a half to Julia, who is taking me on card; the first time I have had my portrait taken. Being very short-sighted, she is obliged to wear spectacles when she draws.

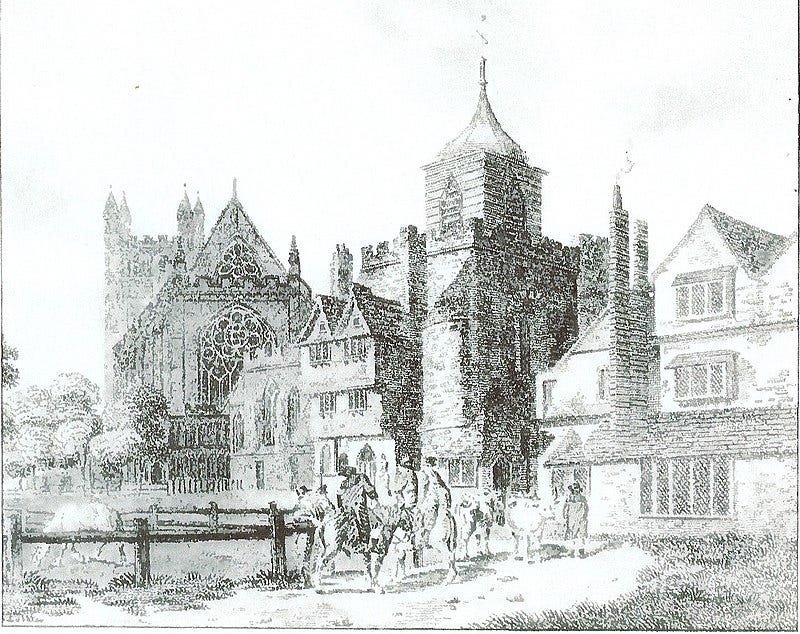

In the afternoon I took a walk alone with Uncle William, who conducted round many parts of Exeter where I had not been. We first went through High Street and into Northernhay, a noble walk round the ruins of the castle, at a considerable elevation, so as to afford a very fine view of the surrounding country. It is shaded with lofty elms several hundred years old, of which no less than forty were blown down in the tremendous gale of Sept. 1, 1833. Besides which, this magnificent walk is further spoilt by what is called an improvement, namely, cutting down several more elms, and thereby leaving an unsightly gap. Nevertheless it is still magnificent. From Northernhay we went down North Street into the Cathedral yard, the first time I had been closer to the Cathedral than Baring Crescent. It is a noble building, though far inferior to Ely. The two towers are rich Norman; the West window is a very beautiful Decorated one; the West front is partly hidden by a fine screen, filled with niches with the statues perfect. We did not enter it.

In the Cathedral Yard is the Institution, which we just stepped into; there are two fine rooms, principally filled with books, and containing some natural and artificial curiosities. Close to the Cathedral is a very frightful modern church, St. Mary Major’s, I believe, executed in the worst possible taste, a mixture of all sorts of styles. From hence we went to Southernhay, another very fine walk, but not equal to Northernhay, and thence to Barn Fields, a row of red brick houses. We then returned to Baring Crescent, entering at the end opposite that which leads to Paris Street. I was rather tired with my walk, and it was late and damp by the time we returned.

During the walk, my Uncle talked to me very kindly on various subjects, especially religious ones, and said a great deal on prayer and devotion which I shall remember, and which will, I hope, be useful to me.

19 October

I took another walk with my Uncle, still longer than the other, and I did a great deal, considering that I had previously walked beyond Heavitree with Julia. With my Uncle, I went first over Mount Radford, a very fine situation, and the houses built with better taste than usual. We passed many rows of buildings in the most ugly, fantastical, non-descript style, a mixture of very barbarous Tudor English with an approach to Grecian and a great resemblance to Chinese; most of the houses are painted or washed a glaring white. The Deaf and Dumb Asylum, and the School-House, which are near each other, are in a very beautiful situation, commanding a noble and extensive view. We then went up the dirty Holloway Street, to Colleton Crescent. This consists of tall, large houses of red brick, quite uniform, and forming a single undivided mass of building, striking, not so much from its own beauty, as from that of its situation. It is perhaps the most elevated part of Exeter, on the brow of a hill, beneath which flows the Ex, while beyond rise high hills, some bare, some wooded. The Ex is not a pretty river at Exeter, the banks are low and flat, and not very much wooded. There is an ugly canal cut beside it, with a few boats and barges on its surface, and new-made roads spoil the country immediately under the hill, but nevertheless the view is beautiful and extensive. In Colleton Crescent Mamma once lived with her family before she was married, when they came to Devonshire for health.

The streets about this part of Exeter are excessively narrow, steep, and dirty, running with liquid mud of deep red colour, and always flanked with an open drain on either side. The town spreads very much, and is increasing in all directions, all the new houses, as I said before, being very ugly and ridiculous.

We then went to the Bedford Circus, which is the greater portion of a circle of old red brick houses. Before it is a garden, on the other side of which is the Bedford Chapel, where Mamma went last Sunday to hear Mr. Scoresby, a very remarkable and excellent character. From thence we came straight home, and were at Baring Crescent by four o’clock.

The most prominent feature in Exeter is everywhere the Cathedral, which rises grandly from the midst of the city. Next to this in importance is St. Sidwell’s Church, which looks well from every point.

I saw for the first time my cousin Mackworth Praed, who dined here at seven o’clock. His little girl, Annie, is staying here for a few days under Aunt Bell’s care. She is about five years old, a clever little chit, with enormously high spirits, and very good-humoured.

Of course I observe little here in the way of natural history. But I saw two or three swallows both to day and yesterday, which is late in the season. Also, I noticed one or two pied wagtails, and I hear the robin sing everyday.

20 October

After, I am sorry to say, a very idle week, I resolved to begin studying again. I took up Morgan’s arithmetic1, and read over carefully some of the earlier part. But I find my brain muddy and rusty with disuse during my long illness, and I was quite fatigued in a very short time. However I shall practice study a little every day, and get myself into the way of it again.

21 October

Phoebe left us this morning, returning to Teignmouth, conveyed by Mackworth Praed, as Mamma was by Bulkely. Her absence makes a great difference; there is fun enough in all of them, but it is all concentrated in her. I suppose we shall have no more thundering shouts of laughter all the evening.

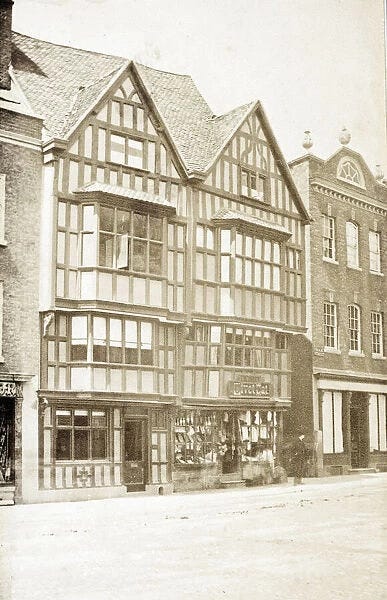

I took another walk with Julia; we went into Exeter by Summerland Street, and went about the town shopping and doing other errands. None of these are worth notice, except one to the Civet Cat, a shop of jewellery and other things, where I saw a most beautiful toy of Genevese construction, of which I have read in Miss Edgeworth’s Rosamond.

It was a little snuff box with a small lid opening in the middle of the top, this lid has an enamelled painting, the subject of which I do not remember, or rather did not observe; according to Miss Edgeworth it is Mont Blanc. The man touching a spring, the enamelled lid flew open, and out sprung a beautiful little humming-bird, glittering with all the hues of the rainbow; which immediately commenced a clear sweet song that lasted about half a minute. While singing, it danced round as if in an ecstacy, opened its beak, heaved its breast, and shivered its wings, so naturally, that it was difficult to imagine that it had not life, yet it was not above an inch in length. When its song was ended, it sunk down into the box, and the lid closed upon it. I was quite delighted with this exquisite piece of mechanism, especially as I have long wished to see it, and indeed have been rather sceptical about its existence.

Mrs. George Trevelyan, a great friend of Aunt Bell and also of Julia Dennis, called this evening. As Julia is exceedingly fond of her, and has often talked to me about her, I was very glad of this opportunity of seeing her. I found her a tall, slim, erect person, of light complexion and hair, with no pretensions to beauty; her deportment extremely quiet and deliberate, her manner of speaking very slow and calm. I understand that she is a very superior person, which I can well conceive.

Mr. Dornford dined here. Amongst other things, he conversed on the subject of gambling, especially as carried on abroad. He said that a friend of his resolved to witness these horrible scenes with his own eyes, so he went to one of the gambling-houses at Paris. As soon as he entered, they took away his stick or umbrella, or whatever he had in hand; this is always done, as if they could not trust them with any thing that could be used as an instrument of violence. Mr. Dornford then described the frightful appearance of the gambling-room; the lurid glare from the lamps above, the various expressions of avarice, envy, rage, despair, on the countenances of the gamblers. He (i.e. Mr. D.’s friend) particularly observed one young man, the expression of whose face was almost frantic. He was evidently one who could not afford to lose, yet he did lose incessantly. He put down a Napoleon on the table, and watched its fate with an eye that glared like that of a maniac. He lost! With trembling hand he put down another. He lost again! Another-he lost for the third time. There was then a convulsive movement of his hand; he thrust it shaking into his pocket, and drew out what was evidently the last piece of money he possessed. He laid it on the table and lost for the last time. He pressed his hands on his forehead in silent despair, and withdrew. The next day, the gentleman saw his body exposed to view according to the custom at Paris; it had been taken out of the Seine.

22 October

I took another walk with my Uncle. We went up Castle Street and into the castle yard. Very little is left of the ancient castle of Exeter except a bit of the wall, and a very picturesque ruin, of Norman date, covered with aged ivy, which looks as old as itself. The castle yard is a neatly kept area, bordered by tall elms; at one end is an ugly modern building, the Sessions house, where my Uncle told me that formerly when the assize balls were held here, they used to dance over the heads of the prisoners, and in their very hearing. This barbarous custom is now disused. We ascended the rampart of the castle, and walked along the top of the wall. As soon as we had mounted, a most splendid view burst upon my sight through the lofty elms rising in front. The whole of Exeter lay outspread before us, and a wide extent of hilly and woody country on every side; we saw the river Ex winding along, and could trace its course down to the sea. I could even see Exmouth and its church situated at the mouth. I saw also the noble Cathedral, the whole length of which was before me. It is certainly a glorious view, though unfortunately obscured to day by a kind of hazy sunshine. I looked at it a long time with great delight; we then descended the rampart, and returned home by the beautiful walk of Northernhay. In Paris Street we [20] †stopped at the house of a man named Frost, a self-taught mechanic of wonderful genius, to see a very remarkable clock, constructed by an Exeter man two hundred years ago. It is a most singular piece of mechanism, having four dial plates; the principal one shows the hour of the day or night; a small one above shows the month, another the day of the month, another the day of the week, another leap-year. The clock has also a band of music, and various figures which act and move at the same time; also a moving panorama representing the course of the sun. The whole forms a very splendid and extraordinary work. It had long been out of repair, and Frost was the only man in Exeter who was able to reput it into order again. It is in the possession of an attorney, who it is said will not sell it for less than 700 pounds.

For scans of some of the manuscripts, plus transcriptions of most of the journals, see here for a wonderful website with lots of additional information. It also discusses which parts of the journals were censored and altered by Emily’s sisters, and why. The brief information about Emily I provided in today’s newsletter barely scratched the surface, so be sure to have a look at this website if you’re interested to know more!

Thanks for reading today’s post! If you enjoy diary diving with me, please consider subscribing to the newsletter or sharing it with other history-loving and/or nosy people. Also, stay tuned for some updates - these diary dives will keep coming every Monday, but I’m considering some additional ideas that would fit in the diary theme. More information soon!

Elements of Arithmetic by Augustus de Morgan, first published in 1830.