Week 39: Josephine Peary

This week, we return again to the Arctic through Josephine Peary's diary.

I’ve been wanting to return to My Arctic Journal, so here’s a full week from Josephine Peary’s diary! You can read my previous posts about her here, here and here.

Josephine Diebitsch Peary (1863-1955) was an author and explorer. She grew up in a family who encouraged her to develop her inquisitive side, and after she married admiral-to-be Robert Edwin Peary in 1888, she would accompany him on an expedition to Greenland in 1891-1892. It was on that expedition that she wrote the journal she would later publish as My Arctic Journal.

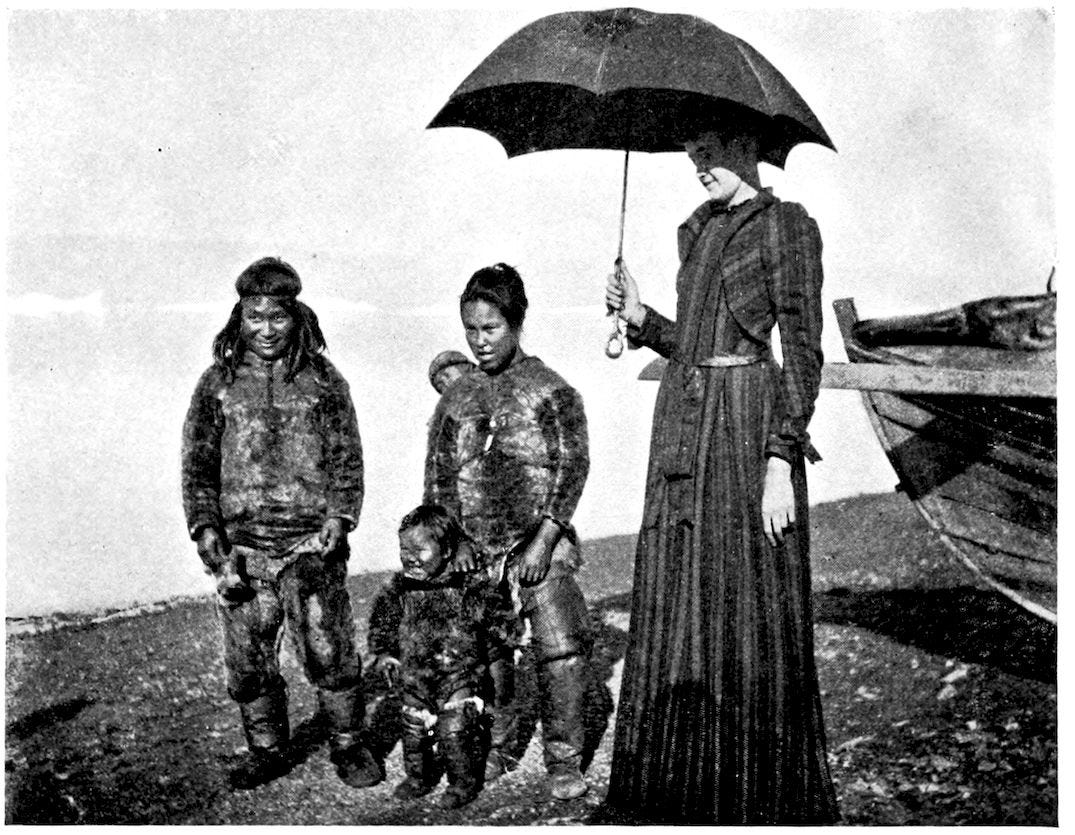

Josephine and the rest of the expedition crew frequently encountered native inhabitants of the area. These encounters have not come up yet in my previous posts about the diary. Although Josephine made a genuine effort to become familiar with local customs and learn the local language, she still described the Inuit she met through a very racist lens, which was of course prevalent at the time. Here’s how she first described Ikwa and his family, who will also be mentioned in this week’s diary entries:

These Eskimos were the queerest, dirtiest-looking individuals I had ever seen. Clad entirely in furs, they reminded me more of monkeys than of human beings. Ikwa, the man, was about five feet two or three inches in height, round as a dumpling, with a large, smooth, fat face, in which two little black eyes, a flat nose, and a large expansive mouth were almost lost. His coarse black hair was allowed to straggle in tangles over his face, ears, and neck, to his shoulders, without any attempt at arrangement or order.

Friday, September 25

Just before we left camp at eleven o’clock, an amusing incident occurred. Ikwa, who had been skirmishing for the past hour, returned in a jubilant frame of mind, and announced his discovery of a cached seal. He asked Mr. Peary if he might bring the seal to Redcliffe in the boat, saying it was the finest kind of eating for himself and family. We could not understand why this particular seal should be so much nicer than those he had at Redcliffe; but as he seemed very eager to have it, we gave him the desired permission, and off he started, saying that he would be back very soon. About half an hour later the air became filled with the most horrible stench it has ever been my misfortune to endure, and it grew worse and worse until at last we were forced to make an investigation. Going to the corner of the cliff, we came upon the Eskimo carrying upon his back an immense seal, which had every appearance of having been buried at least two years. Great fat maggots dropped from it at every step that Ikwa made, and the odor was really terrible.1 Mr. Peary told him that it was out of the question to put that thing in the boat; and, indeed, it was doubtful if we would not be obliged to hang the man himself overboard in order to disinfect and purify him. But this child of nature did not see the point, and was very angry at being obliged to leave his treasure. After he was through pouting, he told us that the more decayed the seal the finer the eating, and he could not understand why we should object.2 He thought the odor “pe-uh-di-och-soah” (very good).

At noon we passed Cape Cleveland, homeward bound, and an hour later reached Redcliffe. The house seemed very cold and chilly after the bright sunshine. Verhoeff, who had been left in charge, greeted us, and we soon had all the oil-stoves going, bread baking, rice cooking, beans heating, venison broiling, and coffee dripping, and at two o’clock all sat down to dinner and then turned in.

Tuesday, September 29

The last three days have been spent in hunting-explorations on the north shore and in preparations for the winter. The stove has been put up, the windows doubled, and the house made generally air-tight. We find the ice in the bay becoming firmer day by day, and in one of our expeditions we found it all but impossible to force the boat through it. Mr. Peary has now left off his splints and bandages, and has even laid aside his crutches. After lunch to-day I started out with a couple of fox-traps, and put them in the gorge about a mile back of the house. The day was fine, and I enjoyed my walk, although I came in for an unpleasant scare. After leaving the traps, I thought I would go over the mountains into the valley beyond, and see if I could find deer. Half-way up, about a thousand feet above sea-level, the snow began to slide under me, taking the shales of sandstone along with it, and of course I went too, down, down, trying to stop myself by digging my heels into the snow and attempting to grasp the stones as they flew by; but I kept on, and a cliff about two hundred feet from the bottom, over which I would surely be hurled if I did not succeed in stopping myself, was the only thing which I could see that could arrest my progress. At last I stopped about half-way down. What saved me I do not know. At first I was afraid to move for fear I should begin sliding again; but as I grew more courageous I looked about me, and finally on hands and knees I succeeded in getting on firm ground. I did not continue my climb, but returned to the house in a roundabout way.

Mr. Peary had the fire started in the big stove, and finds that it works admirably. The trouble will be to keep the fire low enough. Ikwa indulged in a regular war-dance at the sight of the blaze, never before having seen so much fire, and for the first few moments kept putting his fingers on the stove to see how warm it was. He soon found it too hot. He has been getting his sledge, dog-harness, spears, etc., in readiness for the winter’s hunt after seal.

Wednesday, September 30

Toward noon Matt came running in shouting, “Here are the boys, sir!” and sure enough Astrup and Gibson were here, bringing nothing but their snow-shoes with them. They were on the ice just a week, and estimate the distance traveled inland at thirty miles, and the greatest elevation reached at 4600 feet. They returned because it was too cold and the snow too deep for traveling. At the same time, they admit that they were not cold while on the march, and they do not think the temperature was more than 10° below zero; but as Gibson stepped on and broke the thermometer on the third day, up to which time the lowest had been –2°, they had no way of telling for certain. Gibson’s feet were blistered, he having forgotten to put excelsior or grass in his kamiks3. He believes that with the moral support of a large party they can easily make from ten to fifteen miles per day.

Thursday, October 1

The day has been fine; the house is gradually assuming a cozy as well as comfortable appearance under Mr. Peary’s supervision. He is about from morning until night, limping a great deal, but he has put aside his crutches for good.4 At night his foot and leg are swollen very much, but after the night’s rest look better, although far from normal. Ikwa went out on the ice to-day for some distance to test its strength. I took my daily walk to the fox-traps, and as usual found no foxes had been near them.

My Arctic Journey can be read in full here on Project Gutenberg.

Here’s an interesting article about Josephine.

If you’d like to learn more about traditional Inuit food, here are two interesting articles (the same as mentioned in footnote 1): Inuit Fermentation: Animal-Based & Archaic and Microbiota in foods from Inuit traditional hunting.

Thanks for reading today’s post! If you enjoy diary diving with me, please consider subscribing to the newsletter or sharing it with other history-loving and/or nosy people. Also, stay tuned for an exciting bit of diary-research I’ve been doing! Yes, I know I’ve been hinting at this for a few weeks now, but it is coming, I promise! And you’ll be the first to know.

P.S.: this goes for all my posts but especially for this one (as I really don’t know much about Greenland or Inuit), if you have any corrections or further knowledge to share, please let me know in a comment!

While I don’t know anything about Inuit diets, I did a bit of research and found that seals, and various fermented foods derived from them, are an important part of traditional Arctic diets. See here for an interesting article about fermented foods in Greenland, and here for an article about microbiota in traditional Inuit foods. I wasn’t there, of course, but I do think it likely that a native inhabitant of the area would have been more knowledgeable about which foods were safe to eat there than a foreign explorer.

Note the infantilising depiction of Ikwa (a grown man being described as a pouting ‘child of nature’).

Kamiks (or mukluks) are soft boots traditionally worn in the Arctic.

Mr. Peary had broken his leg two months prior to this.